Claire Regnault, Te Papa's Senior Curator, NZ Culture and History

Writing for Elle magazine in March 2023, writer Gabby Wilson declared that we were in ‘the Era of Shipwreck Chic’.

The vibe is ripped seams and broken nails and sweating through your blowout. Blood stains on your shirt, comfort in your sins. The carnal elegance of not just surviving the shipwreck, but embracing all the ways you might actually be one yourself.[1]

A year earlier, the magazine The Face had observed that sea wreck motifs reflected a darker side of collections inspired by the ocean at a time when global sea levels were rising and soaring temperatures were bringing the climate crisis into sharper focus.[2]

Surviving items in Te Papa and Canterbury museums’ collections, however, bring ‘shipwreck chic’ back to reality. The people that made or wore them, may have been shipwrecked, but they didn’t want to look like one!

A dainty jacket and natty hat

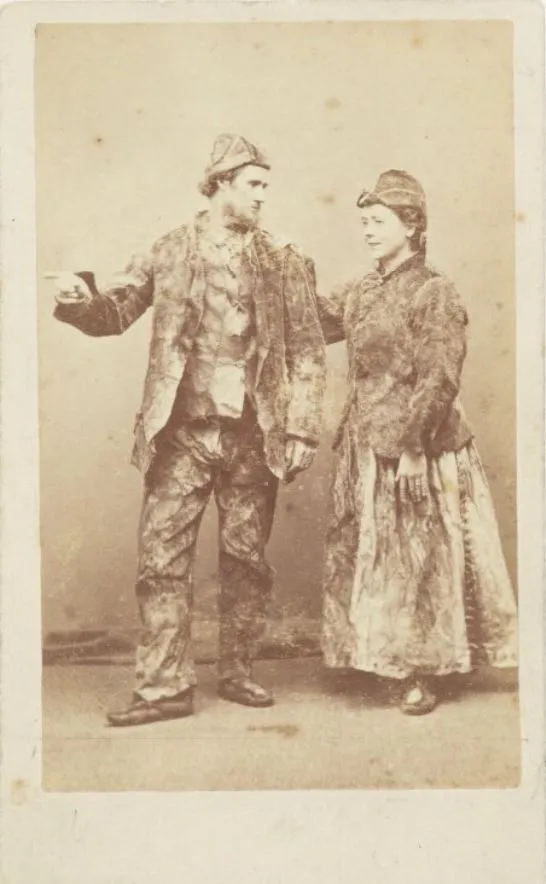

This carte de visite depicts real life castaways Joseph and Mary Ann Jewell (née Hewitt).

The Jewells hailed from Victoria, Australia. They had the great misfortune of being on the General Grant when it was wrecked off Disappointment Island, in the remote sub-Antarctic Auckland Islands in May 1866. The ship was en route to London with a valuable cargo of wool, hides and gold, some of which belonged to the Jewells.

The Jewells and thirteen other men made it to land. Eighteen months later, in November 1867, the couple and eight other survivors were rescued from Enderby Island by the crew of the Amhurst. Their appearance took their rescuers back a little.

The party had believed that the Victorian Government had placed some stores on the island in case of ship wreck the year prior, but their search was unsuccessful. As their clothes deteriorated, Mary Ann and fellow survivor James Teer, a gold miner, began to fashion garments out of seal skins for the survivors, using needles carved from albatross bone with a penknife.

But as James Jewell later wrote to his father, when they finally arrived they ‘soon had us out of our seal-skin clothes and supplied with everything of the best’.[3]

For Catherine Rolfes, a dressmaker on the West Coast, however, the style and quality of Mary Ann’s shipwreck chic was something to be marvelled at: ‘I saw the garments in which she landed in New Zealand … [they] consisted of a gored skirt, & dainty jacket, with a natty little cap, & shoes with the fur towards the feet; she also had an undergarment with the fur turned inside for the cold was great; all these were very neatly sewn.’[4]

The garments not only saved Mary Ann’s life, but also helped her make-up for some of the fortune the Jewells had lost at sea. She is said to have earned as much as £600 delivering lectures about the ordeal while dressed in her sealskin outfit.[5]

While Mrs Jewels’ garments do not survive, the Canterbury Museum holds a pair of seal skin shoes made by a Finnish sailor called Michael Puh, who was on the Dundonald when it was wrecked on Disappointment Island over forty years later in 1907.

Spring poets’ and new toggery

Due to the number of shipwrecks around the Great Circle shipping route between Australia to Europe, the New Zealand government established a number of relief depots on the sub-Antarctic Islands, so that survivors would not experience the level of hardship that the Jewells and their fellow survivors had to bear. The depots were stocked with guns for hunting, food, blankets, and warm clothing including suits, flannel shirts, woollen drawers, socks and boots along with needles and thread, sail needles, twine.[6]

Although Disappointment Island lived up to its name, the sailors from the Dundonald eventually found such a depot on a nearby island, which enabled them to exchange their worn out clothes for new:

“There was a good boat at the depot, but no sails, so we cut up our clothes to make a sail… We had found clothes at the depot and exchanged them for what we were wearing, and we had also cut each other's hair and beards, which during the seven months we were on the other island had grown so long that we looked like a lot of 'spring poets.' As we got near our old camp our mates did not know us in our new 'toggery' and they thought we were sealers.”[7]

The clothes were probably similar to this suit, which was bought back from an abandoned depot on Snares Island in 1947 by Dr Robert Falla, the Dominion Museum’s director. He was in the sub-Antarctic Islands on a scientific research trip. With permission, he bought back five coarse woollen three-piece suits, one of which bears a ‘Manufactured in New Zealand’ tag and a zinc box of men’s leather boots. While perhaps to our eyes, a three-piece suit does not seem the most practical of items to leave, it mirrored working class men’s dress at the time, although was better in quality.

Stocked for the unfortunate, the depots suffered from looting - an act which was deemed a ‘dastardly form of theft’ – by opportunists.[8] To this end, some believe that the provided suits were made in a distinctive patterned tweed in order to make them recognisable to officials on the mainland should they be stolen!

When Dundonald survivors were rescued they were wearing a combination of depot clothing and items, such as the above shoes and caps fashioned from seal skin and untanned cowhide.[9]

Little did these shipwrecked souls know that their crafty threads would provide inspiration to fashion designers generations later, though this trend demonstrates the ingenuity required to make-do in a world where mother nature is throwing curve-balls left right and centre.

If shipwreck chic isn’t your thing, perhaps you should check out the other big sea themed fashion trend of 2023 - #mermaidcore, complete with pearl and iridescent accents.

[1] https://www.elle.com/fashion/trend-reports/a43399718/shipwreck-chic-trend/

[3] Reproduced in ‘Marooned for 18 months — struggle and hope’, Press, 20 January 1978, p. 9 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/CHP19780120.2.106

[4] Ibid., pp. 73–74.

[5] Philip Boulton, ‘Rescue messages: The survivors – a new life.’ http://wreckofthegeneralgrant.com/page17.htm.

[6] Evening Star, 24 May 1905, p.1. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/ESD19050524.2.6

[7] ‘A Castaway’s Story’, Auckland Star, 2 December 1907, p. 5. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/AS19071202.2.44.3

[8] ‘Government’s Island Depots’, Mataura Ensign, 27 May 1908, p. 3. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/ME19080527.2.14.2

[9] ‘Castaways Rescued’, Hawera & Normanby Star, 2 December 1907, p.5. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/HNS19071202.2.21.1