by Kelly Dix, Online Engagement Manager, Digital NZ

Cork, kapok, rubber, and foam - these humble materials have saved untold lives through their use in floatation devices. As an island nation, Aotearoa New Zealand has a long history of its inhabitants arriving by sea. On arrival, the ocean and Aotearoa’s many bodies of freshwater continued to be a source of food, transport, income, and recreation. Various forms of personal floatation devices, including air-filled containers, inflated animal skins or buoyant pieces of wood, have long been used to help prevent drowning.

A ‘life preserver’ jacket made from cork was widely advertised in the late 19th century. Their popularity increased as ships began to be made from heavy iron rather than wood because wood could provide a life raft of sorts for shipwrecked sailors whereas iron sunk. However, there were no requirements to provide or wear them, leaving responsibility for their use to the individual. An advertisement in the New Zealand Herald (19 November 1878, asks ‘Why risk your lives when you can obtain a Life Preserver?’.

The cork life jackets were effective if worn, but their stiff and bulky design meant that most seamen found them difficult to work in.

There were no life preservers on board the HMS Orpheus when it ran aground on the sandbar at the entrance to Auckland’s Manukau Harbour in 1863. The ship’s lifeboats weren’t sufficient for a mass rescue and 189 of the 259 men drowned — mostly British soldiers on their way to New Zealand to fight in the Waikato Land Wars.

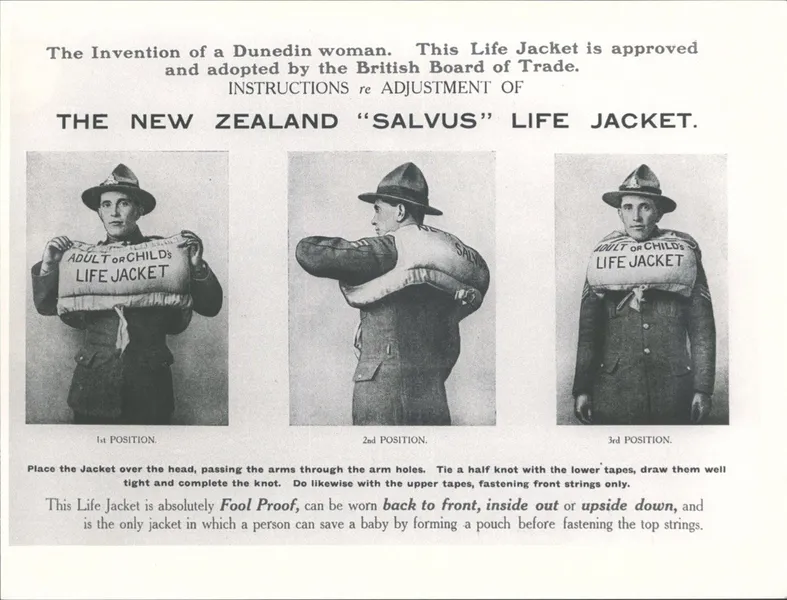

Not long after the accident, the mother of one of the men presumed drowned gave birth to a daughter. The baby, named Orpheus, grew up keenly aware of the dangers of the sea. The family immigrated to New Zealand in 1870 and Orpheus later married a mariner. Two tragic events in 1912 — the drowning of another brother off the Otago coast and the sinking of the Titanic — motivated Orpheus to design a life preserver from a new material, kapok. When travelling across the Pacific with her husband, she had observed the floatation qualities of a fibre found in the seedpod of the kapok tree.

Her design was a cotton vest filled with kapok fibre that was easy to put on in an emergency. Named the ‘Salvus’ (Latin for 'safe'), it was approved by the British Board of Trade in 1918 and was mass-produced around the world.

The Salvus was worn by the British Navy and was widely adopted by ships and steamer services all over the world.

However being a natural fibre, kapok was prone to deterioration particularly in damp conditions. And the canvas outer shell, though sturdy, had the downside of being rough on the skin and often caused chafing. These issues prompted the invention of a new style of life jacket which became standard issue during the Second World War.

The Mae West style lifejacket

Pilots flying in the air force needed a smaller life preserver that could fit comfortably in small spaces. Patented in 1928 by an American designer Peter Markus, the rubber Inflatable Life Preserver, known as the ‘Mae West’, was worn flat on the chest until needed. Simple straps under the arms and across the back allowed pilots and aerial gunners to move freely. When activated, the inflatable part across the chest kept the wearer floating face-up in the water.

The transition also occurred in the fledgling civilian aviation industry. Kapok filled vests were replaced by self-inflating ones. Safety demonstrations introduced for passengers demonstrating how to wear kapok vests correctly were updated for the inflatable design.

Kapok vests were still being used until the 1960s when synthetic foam life jackets provided a cheaper and more comfortable option for boaties and mariners. They were also better at keeping you afloat in water. Foam is still used in life jacket production, although there was a move to closed cell foam technology in the 1970s.

Inflatable life jackets are also worn by boaties but the latest versions are inflated with gas and require regular maintenance checks. The advantage of this style over foam is that they are designed to flip the wearer face-up if they are unconscious.

Wearing a personal flotation device can be a lifesaver, but adding a few extra safety items can make a big difference in rescue situations by reducing the time you spend in the water. Attachable whistles and lights can help search and rescue teams locate you more easily.

In the waters of Aotearoa, staying safe is non-negotiable. Whether you're out for a calm paddle or a more adventurous ride, the need for a life jacket is real. Although technology has changed the construction, the message is still the same as in 1878: Why risk your life when you can wear a life preserver?

Featured organisations

-

Organisation | Whare Taonga

Howick Historical Village

-

Organisation | Whare Taonga

Museum of Transport and Technology (MOTAT)

-

Organisation | Whare Taonga

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

-

Organisation | Whare Taonga

New Zealand Maritime Museum Hui Te Ananui a Tangaroa

_

-

Organisation | Whare Taonga

Puke Ariki

-

Organisation | Whare Taonga

National Army Museum Te Mata Toa

-

Organisation | Whare Taonga

Auckland War Memorial Museum