Hana Pera Aoake (Ngāti Hinerangi, Ngāti Mahuta, Waikato/Tainui, Tauranga moana, Poutini Ngāi Tahu) is Miriama Jean’s mum, an artist and writer and the Museum curator at the Sir James Fletcher Kawerau Museum.

Leading up to Matariki I have been reflecting a lot about the idea of ‘home’ and the different places I have lived, and the changes that have been happening in my life, especially moving from Ōtepoti to Kawerau.

I am really missing my whānau who are overseas. It’s been very strange not having my parents in Waikouaiti, which is just north of Ōtepoti and been a base for our whānau for many years. It’s weird not to have a reason to go back. I’ve been re-reading Alice Te Punga Somerville’s book, Always Italicise: How to write while colonised and thinking a lot about one poem titled, Te Kawa a Māui farewell where she writes, ‘I’ve never been an ahi kā kinda girl’ and I think this really describes my relationship to home, which has always been mobile and transient.

With this in mind I found myself doing searches through the Kōtuia collections for places I missed or had a connection to. As an artist, I am always more drawn to art and photography than objects.

Waikato River, 1980s, Brian Brake, Te Papa

The Waikato awa is my tūpuna awa. Every Matariki I try to visit my Nana and namesake, Pera who is buried on Taupiri maunga. My Nana looks out over the awa. In winter, I feel like it's always cloaked in Hinepūkohurangi and looks otherworldly. In this photograph I feel like I’m waiting for Hine-nui-te-pō to appear as a kind of Charon, the ferryman on the river Styx waiting to take the souls of the dead to Te Pō. Over Matariki I will be thinking of the people we have lost and how much I love and miss them.

I have been drawn to so many of Brian Brake’s photographs since moving back to Te Ika-a-Māui. He took such beautiful photographs of even the most seemingly mundane places, objects and subjects. In our collection at the Kawerau museum we have a series by him known as the Tasman portraits, which are a series of crisp colour photos of Tasman mill workers from the late 1970s- early 1980s.

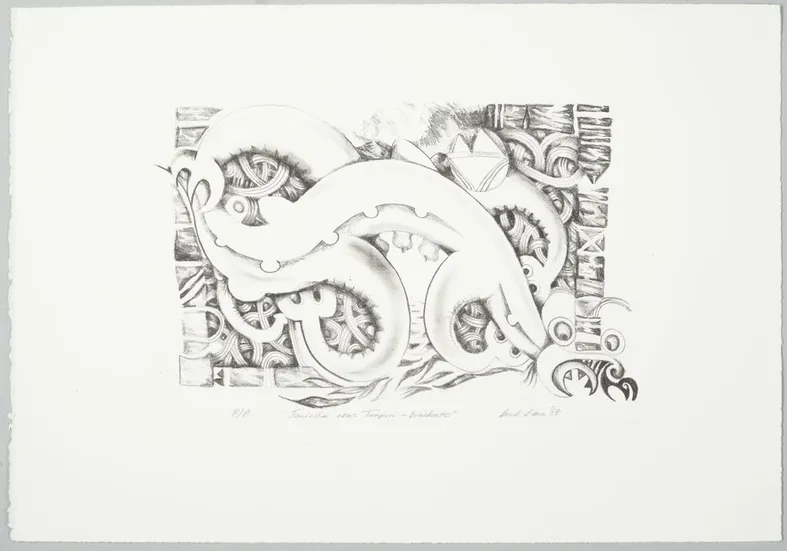

Taniwha near Taupiri - Waikato, 1988, Buck Nin, Te Papa

One of the most famous whakataukī about the Waikato awa is, ‘Waikato taniwha rau, he piko te taniwha, he piko he taniwha’, which roughly translates to ‘Waikato of a hundred taniwha on every bend a taniwha’. For people who belong to the Waikato river taniwha are often seen as kaitiaki, but can also be benevolent. For me personally I believe that taniwha live all along the Waikato and that perhaps many have been displaced since colonisation, considering a lot of the repo in the Waikato has been drained to make farmland and that's where taniwha used to live. ‘Waikato taniwha rau, he piko te taniwha, he piko he taniwha’ also speaks to the mana of the people who belong to the Waikato awa.

I’ve always really loved Buck Nin’s mahi toi and always found his work really joyful. I was drawn to this obviously because of my whakapapa ties to the Waikato awa and Taupiri maunga. I love lithography which is a very old form of printmaking. The word is Greek and comes from ‘lithos’ meaning ‘stone’ and ‘graphein’ meaning to ‘scratch’ or write. It's a process where a design is drawn onto a flat stone (or metal plate) using a lithograph crayon and then usually gum arabic or a kind of acid is rubbed on which will stick to the drawing before it comes out as a print.

I would’ve really liked to have met Buck Nin. I read somewhere that he was a bit of an entrepreneur and had a business exporting dried meat to China, but also developed a microwave hangī business. I believe he was based in Kerikeri for a number of years as a high school teacher and like a lot of other Māori artists of his generation he undertook the Māori art education programme developed by Gordon Tovey.

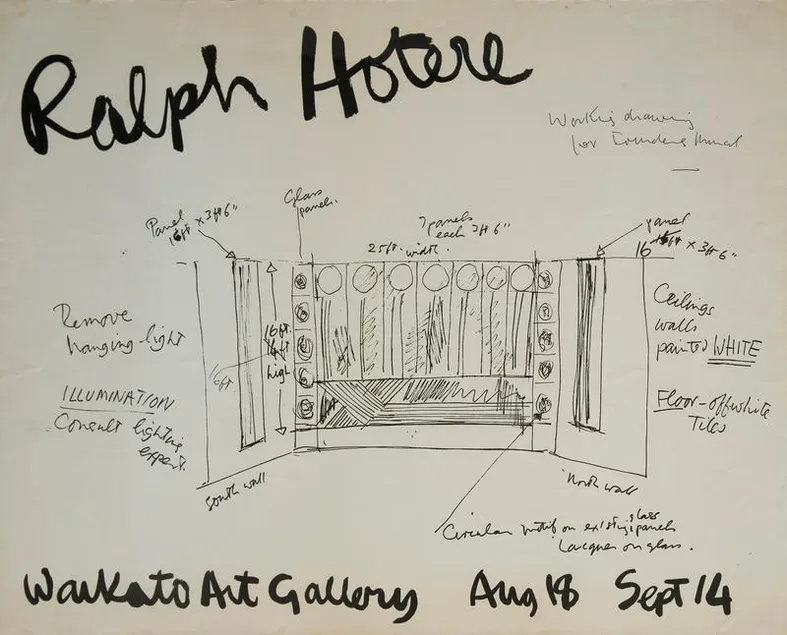

The first New Zealand artist that was really important to me was Ralph Hotere. Hotere also reminds me of Ōtepoti which will always be a place that feels most like home, because it’s the place I spent my most formative years. Growing up in Ōtepoti you take for granted how often you come across his work, whether it’s at a friend's house in Port Chambers, Carey’s bay pub, the public art gallery, the university or the hospital. When I see his work he reminds me of the ebbing tides at Carey’s bay, of collecting cockles at Waitapu bay, swimming at Waikouaiti beach… It reminds me of home. It actually makes me feel very emotional seeing Hotere’s work, as I got to meet him once when I was about twenty shortly before he passed away and he was very unwell but very funny, and kind.

I really love all of his work and I think he was the first Māori artist whose work I deeply connected to, I think because he redefined what it meant to be an artist. I have this protectiveness over his work and how it’s framed by pākehā art historians as evidence of him rejecting being Māori and being solely influenced by European modernists. This isn’t at all what his work is doing. He just didn’t want to be pigeonholed as a ‘Māori artist’, but rather he was always adding to his kete and wanted to be an artist (who happened to be Māori.) He will always be an artist who demanded complication, opacity and who will never be defined as just Māori.

There’s a great a documentary on Archives NZ and youtube after he was commissioned by the Hamilton City Council to make the Founders Memorial Theatre. Hotere's mural was the result of a two stage competition organised by the Hamilton City Council and the Queen Elizabeth II Arts Council. In the documentary multiple people talk about Hotere’s work but he does not, which he was famous for… not even giving an artist statement. I particularly love the way Hone Tuwhare spoke about his work and their friendship.

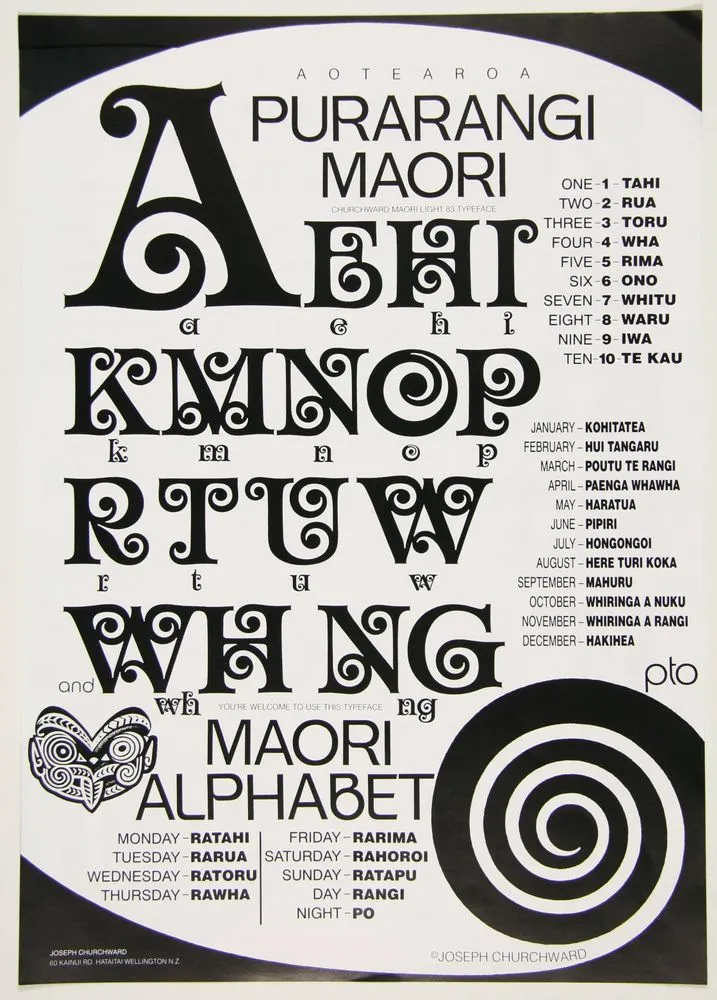

Churchward Aoteraoa Purarangi Alphabet Poster, Joseph Churchward, Te Papa

This poster is incredible! I have used Joseph Churchward’s typography for a number of years. Churchward was born in Samoa and developed a number of fonts which are used all over the world. There is something really beautiful and celebratory for me about his work. There is a nostalgia too, which is why I used Churchward Māori and Churchward newstype in my first book of poetry and essays. I really wanted it to feel timeless and to visually signpost that this was work by a Māori writer from the Pacific… if this makes sense. At the moment for some projects I am working with Churchward Samoa, Churchward Design and Churchward Typestyle. Typography and design have always been really important parts of any work I sign my name on for.

Last year for an exhibition my friend Shannon Te Ao curated we (Kei te pai press - a project I work on with my partner Morgan Godfery) used Churchward Māori for a newspaper of Māori writing we reprinted which we called Te Kotahitanga. We worked with a Māori designer named Kimi Moana Whiting who really got that. I love reading about how ink designs were distributed before digital technology. It would’ve taken him so long to create a new typeface.

I have been thinking a lot about how Matariki is acknowledged across Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa, so for instance in Samoa it is known as Mata’ali’i, so thinking about a Samoan typographer making a Māori typeface to me really speaks to the ongoing exchanges between Māori and our cousins across the great ocean. My partner and daughter are both Māori and Samoan, which has been informing a lot of my thinking about exchanges of knowledge and culture. In many ways our home is also the ocean, because it’s as the Tongan writer Epeli Hauʻofa (quoting Teresia Teaiwa) wrote “We sweat and cry salt water, so we know that the ocean is really in our blood.” One great thing about living in Kawerau is that my daughter now spends a lot of time with her Samoan koro and it demonstrates to her that she belongs to Te Moana-nui-a-kiwa

Māori children and teacher in a classroom, circa 1990, Glenn Jowitt, Te Papa

I came across this photograph a little while ago when I was thinking about the work that Hana Te Hemara and Ngā Tamatoa did around the Māori language petition and to push for the revitalisation of te reo Māori in schools. I love it because of the acid washed denim jacket and colours the tamariki are wearing, but also seeing Te reo Māori up on the blackboard (The kaiako’s perm is also great).

My daughter goes to Te Kōhanga reo o ngā mokohuia o te Rautahi in Kawerau and it’s honestly so special that she will know te reo Māori. Although she is only nineteen months old she is already able to distinguish between Te reo Māori and te reo Pākehā. In the last month she has begun talking so much more in both languages and I am so happy that it’s just going to be normal for her to hear both, because that certainly hasn’t been my experience. I love belonging to a kōhanga and being with other parents who are on a similar te reo Māori journey of reclamation, which holds a lot of mamae, but also is really beautiful and healing. It’s really exciting for our whānau to see what the future brings, but for now my daughter learning her ancestral language on her whenua in view of her maunga feels like the best place for us to call home (for now).

Featured organisations

-

Whare taonga | Organisation

Waikato Museum Te Whare Taonga o Waikato

-

Whare taonga | Organisation

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

-

Whare taonga | Organisation

Sir James Fletcher Kawerau Museum